The Integrated Resource Plan 2019: A promising future roadmap for generation capacity in South Africa

Why is there buzz around the IRP? What is its relevance?

The integrated resource plan (IRP) is an electricity capacity plan which aims to provide an indication of the country’s electricity demand, how this demand will be supplied and what it will cost. On 6 May 2011, the then Department of Energy (DoE) released the Integrated Resource Plan 2010-2030 (IRP 2010) in respect of South Africa’s forecast energy demand for the 20-year period from 2010 to 2030. The IRP 2010 was intended to be a ‘living plan’ that would be periodically revised by the DoE. The IRP 2010 stated that at the very least the IRP should be revised by the DoE every two years. However, this was never done and resulted in an energy mix that failed to adequately meet the constantly changing supply and demand scenarios in South Africa, nor did it reflect global technological advancements in the efficient and responsible generation of energy.

In terms of the Electricity Regulation Act, No 4 of 2006 (ERA), the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA) is required to issue rules designed to implement the IRP. It is notable that NERSA has not issued any such rules since the IRP 2010 was first published. Instead, the DoE implemented the IRP2010 by issuing Ministerial Determinations in line with s34 of the ERA in order to give effect to the procurement of new generation capacity.

On 27 August 2018, the then Minister of Energy published a draft IRP which was issued for public comment (Draft IRP). This lengthy public participation and consultation process has culminated in the issue of the overdue IRP2019 which updates the energy forecast from the current period to the year 2030.

What is the difference between the IRP and an IEP?

The National Energy Regulator Act, No 34 of 2008, places an obligation on the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy to develop, and on an annual basis, review and publish the Integrated Energy Plan (IEP) in the Government Gazette. The IEP is meant to serve as the guide for energy infrastructure investments, take into account all viable energy supply options and guide the selection of the appropriate technology to meet energy demand. There has been no IEP published since the enactment of the National Energy Regulator Act, and the IRP2019 gives no indication as to when such IEP will be published. In fact, it is interesting that the “Integrated Energy Plan” has been defined but is not mentioned further in the IRP2019.

Generation capacity procured and developed under the IRP2010

Since the promulgated IRP2010, the following capacity developments have taken place:

- A total 6,422MW under the government led Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Programme (RE IPP Procurement Programme) has been procured, with 3,876MW currently operational and made available to the grid.

- In addition, IPPs have commissioned 1,005MW from two Open Cycle Gas Turbine (OCGT) peaking plants.

- Under the Eskom build programme, the following capacity has been commissioned: 1,332MW of Ingula pumped storage, 1,588MW of Medupi, 800MW of Kusile and 100MW of Sere Wind Farm.

In total, 18,000MW of new generation capacity has been committed to.

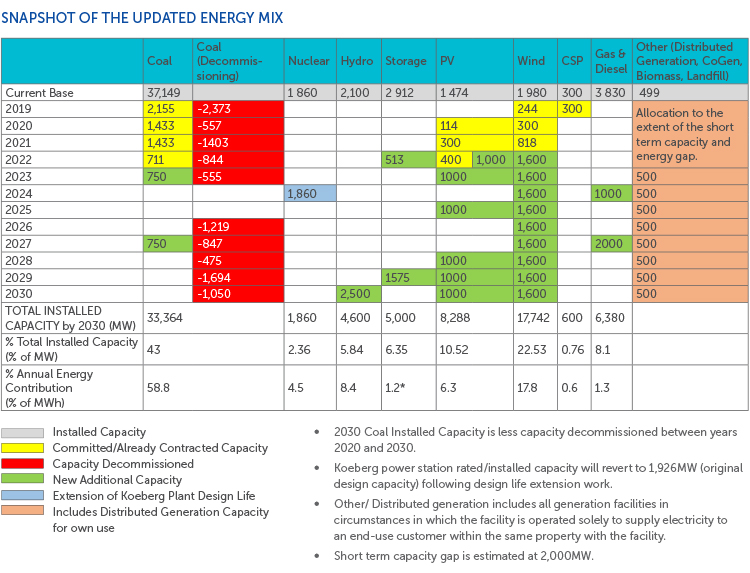

Provision has been made for the following new additional capacity by 2030:

- 1,500MW of coal;

- 2,500MW of hydro;

- 6,000MW of solar PV;

- 14,400MW of wind;

- 1,860MW of nuclear;

- 2,088MW for storage;

- 3,000MW of gas/diesel; and

- 4,000MW from other distributed generation, co-generation, biomass and landfill technologies.

The changes from the Draft IRP capacity allocations see an increase in solar PV and wind, and a significant decrease in gas and diesel; and new inclusions include nuclear and storage. It is notable that embedded generation (previously described as generation for own use allocation) has effectively been replaced with the concept of “distributed generation” (described as all generation facilities in circumstances in which the facility is operated solely to supply electricity to an end-use customer within the same property with the facility) and allocated with other technologies of co-generation, biomass and landfill gas. Once again there has been no allocation for solar CSP.

The IRP2019 explains that it is developed within a context characterised by very fast changes in energy technologies, and uncertainty with regard to the impact of the technological changes on the future energy provision system. It further states that this technological uncertainty is expected to continue and calls for caution on the assumptions and commitments for the future in a rapidly changing environment. Accordingly, the approach taken is that long range commitments are to be avoided as much as possible to eliminate the risk that they might prove costly and ill-advised. At the same time, there is also a recognition that some of the technology options will require some level of long-range decisions due to long lead times.

Accordingly, what we see is an IRP2019 with a fair amount of flexibility which identifies potential risk areas and seeks to provide mitigation measures should the risk materialise.

Renewable Energy

The IRP2010 contained capacity allocations for electricity generated from renewable technologies, and it is against these allocations that the then Minister of Energy issued Ministerial Determinations for renewable energy, which included the technologies of solar PV, wind, solar CSP, landfill gas, biomass, biogas and shall hydro. To date, four bidding rounds have been completed for renewable energy projects under the RE IPP Procurement Programme.

The most dominant technology in the IRP2019 is renewable energy from wind and solar PV technologies, with wind being identified as the stronger of the two technologies. There is a consistent annual allocation of 1,600MW for wind technology commencing in the year 2022 up to 2030. The solar PV allocation of 1,000MWs per year is incremental over the period up to 2030, with no allocation in the years 2024 (being the year the Koeberg nuclear extension is expected to be commissioned) and the years 2026 and 2027 (presumably since 2,000MW of gas is expected in the year 2027).

The IRP 2019 states that although there are annual build limits, in the long run such limits will be reviewed to take into account demand and supply requirements.

Coal

Up to the end of 2030, the new capacity demand is primarily driven by the decommissioning of the existing coal-fired plants and the IRP2019 contains a detailed decommissioning schedule. A further 24,100MW of coal power is expected to be decommissioned in the period beyond 2030 to 2050.

The IRP2019 states that coal will continue to play a significant role in electricity generation in South Africa in the foreseeable future as it is the largest base of the installed generation capacity. However, new investments will need to be made in more efficient coal technologies of High Efficiency Low Emissions technology (HELE) including power plants with carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) to comply with climate and environmental requirements. HELE coal technologies include underground coal gasification, integrated gasification combined cycle, carbon capture utilisation, supercritical and ultra-supercritical power plants, and similar technology.

The stance adopted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and financial institutions in regard to financing coal power plants, is a consideration upon which the support of HELE technology is predicated.

The IRP2019 mentions the already procured IPP coal projects and states that it shows a business case for modular and smaller power plants (300MW and 600MW). However, it is noted that there is risk of 900MW of coal procured not materialising due to financing and legal challenges.

Also included is 750MW of coal to power in the year 2023 and a further 750MW in the year 2027. It is stated that all new coal power projects must be based on high efficiency, low emission technologies and other cleaner coal technologies. The assumption in the IRP2019 is that all new coal to power capacity beyond the already procured 900MW will be in the form of clean coal technology.

Gas

The most significant reduction in capacity allocation from the Draft IRP has been the gas allocation, reducing from the previous 8,100MW of new additional capacity to 3,000MW, with an allocation of 1,000MW in the year 2023 and 2,000MW in the year 2027.

It would appear that the lead times on the planned gas-to power programme has been adjusted taking into account the availability of gas resources in the short to medium term, locational issues like ports, environment, transmission etc. The IRP2019 states that this represents low gas utilisation, which will not likely justify the development of new gas infrastructure and power plants predicated on such sub-optimal volumes of gas. Consequently, the development of gas infrastructure will be supported.

The immediate focus is on the conversion of the diesel-powered peakers on the east coast of South Africa, as this is taken to be the first location for gas importation infrastructure and the associated gas to power plants. Availability of gas provides an opportunity to convert to CCGT and run open-cycle gas turbine plants at Ankerlig (Saldanha Bay), Gourikwa (Mossel Bay), Avon (Outside Durban) and Dedisa (Coega IDZ) to gas.

Distributed Generation

The IRP2019 allocates 500MW per annum for “Other [Distributed Generation, Co-Gen, Biomass, Landfill]” commencing in 2023. For the period 2019-2022, there is no prescriptive MW allocation and instead the IRP2019 simply provides for an ‘allocation to the extent of the short term capacity and energy gap.’ The short term capacity gap for the period 2019 -2022 is estimated at 2,000MW in the footnote to Table 5 [IRP2019].

The MW allocation in the IRP2019 of 500MW commencing from 2023 for other distributed generation in the manner prescribed is an increase from what was previously put forth in the Draft IRP and is a welcome development aimed at stimulating the growth of the own generation and captive power market in South Africa.

The term embedded generation, previously defined and referenced in the Draft IRP, has been replaced with the term ‘Distributed Generation’ referring to “small-scale technologies to produce electricity close to the end users of power”. There is no specific limitation on the installed capacity of the generation facility. Rather, the determining factors are the location of the generation facility and that the technology used is considered to be small scale technology.

Other Distributed Generation for the purpose of the column titled “Other [Distributed Generation, Co-Gen, Biomass, Landfill]” in Table 5 [IRP2019] refers to ‘generation facilities in circumstances where the facility is operated solely to supply electricity to an end user customer within the same property with the facility’ and includes distributed generation capacity for own use. This excludes generation facilities where the electricity generated is wheeled to an end user not located on the same property or where the electricity is supplied to multiple end users.

Unfortunately, there is no guidance as to what is considered to be ‘small scale technologies’ for the purpose of qualifying as ‘other distributed generation’ and there is no specific reference to the installed capacity of the generation facility.

Hydro

The Draft IRP included 2,500MW of hydro power in 2030 to facilitate the RSA-DRC treaty on the Inga Hydro Power Project, in line with South Africa’s commitments contained in the National Development Plan to partner with regional neighbours. The Grand Inga Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is repeated in the IRP2019 but acknowledges the concerns raised about risks associated with a project of this nature. The clear statement is made that in principle South Africa does not intend to import power from one source beyond its reserve margin, as a mechanism to de-risk the dependency on this generation option.

Nuclear

One of the most significant departure points from the Draft IRP is the inclusion of nuclear into the energy mix. Since the Koeberg Power Station reaches the end of its design life in 2024, South Africa has made a decision to extend its design life. The approach taken, as with coal, is that small nuclear units will be a more manageable investment than a fleet approach. The IRP2019 includes a capacity of 1,860MW in the year 2024 specifically allocated for the extension of the Koeberg design life by another 20 years by immediately undertaking the necessary technical and regulatory work.

The IRP2019 also touches on the expansion of the nuclear power programme into the future and repeats the phrase commonly echoed by the South African government that such technology be developed at a “scale and pace” that flexibly responds to the economy and electricity demand. Since the IRP 2019 states that upfront planning with regard to additional nuclear capacity is a requisite given a lead time of more than 10 years, this opens up the door for the planning phase of a new nuclear programme to commence imminently even though there has been no capacity allocation for the new build programme as yet. The IRP2019 records a decision to commence preparations for a nuclear build programme to the extent of 2,500MW at a pace and scale that the country can afford.

Storage

The importance of storage is recognised, given the extent of the wind and solar PV option in the IRP2019. The IRP2019 notes that Eskom is already preparing to pilot an energy storage-technology project based on batteries. The pilot will enable the assessment and development of the technical applications and benefits, the regulatory matters that relate to a utility-scale energy storage technology and the enhancement of assumptions for future iterations of the IRP.

Role of Eskom

The extracts pertaining to the role of Eskom give interesting insight as to the future expected role of Eskom in energy generation. In particular, Eskom’s role as a Buyer under s34 of the ERA will have to be reviewed, taking account the ramifications once the generation, transmission and distribution functions are separated. The financial standing and credibility of any new buyer, and the commensurate government support provided to such buyer will be critical to the success of further IPP programmes and projects.

It is also hinted that Eskom may be a generator in future competing with private sector generators. This is reflected in the statement that a strategy must be developed as part of the unbundling to enable Eskom to participate in the development of new generation capacity in line with the IRP2019.

The road ahead…

Given the flexibility that the IRP2019 has, it is critical that the South African government and policymakers keep their finger on the pulse. It is therefore important that the IRP 2019 is approached as it was intended to be, as a living document that is regularly reviewed and updated. In addition, there are many constructive decisions and tasks which need immediate attention. The plan is done, it’s now time for implementation.

The information and material published on this website is provided for general purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. We make every effort to ensure that the content is updated regularly and to offer the most current and accurate information. Please consult one of our lawyers on any specific legal problem or matter. We accept no responsibility for any loss or damage, whether direct or consequential, which may arise from reliance on the information contained in these pages. Please refer to our full terms and conditions. Copyright © 2026 Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr. All rights reserved. For permission to reproduce an article or publication, please contact us cliffedekkerhofmeyr@cdhlegal.com.

Subscribe

We support our clients’ strategic and operational needs by offering innovative, integrated and high quality thought leadership. To stay up to date on the latest legal developments that may potentially impact your business, subscribe to our alerts, seminar and webinar invitations.

Subscribe