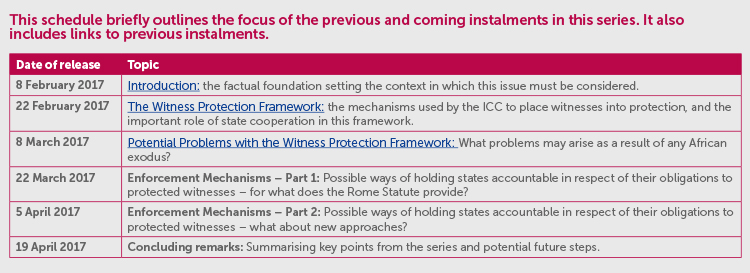

Enforcing ICC witness protection obligations: Part 1

The Rome Statute itself provides for two courses of action in the event of non-compliance:

1) referral to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC); and

2) referral to the Assembly of States Parties (Assembly).

Referral to the UNSC

Article 87(7) of the Rome Statute provides that where a States Party (or former States Party) fails to comply with the duty to cooperate, the International Criminal Court (ICC or Court) may refer the matter to the UNSC. However, this course of action is only available where the matter before the Court was referred to it by the UNSC (as is the case with Darfur). The UNSC will only refer a matter to the Court where the state concerned is not an ICC member state; and the state has not accepted the jurisdiction of the Court in respect of the issue under investigation. Therefore, this is not a readily-available route for the Court to pursue and will seldom find application.

Where a matter does make it to the UNSC for consideration, it will come up against the usual UNSC problem of the ‘permanent five’ veto powers. That is, the United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia and China each hold the power to veto any vote of the UNSC as a whole. It is widely accepted that this veto power can be used as a political tool. Of these five states, only Russia is an ICC member state (and, as mentioned in the first alert, it has indicated its intention to begin the withdrawal process).

Cooperation to protect the lives of witnesses may, therefore, be subjected to the political willpower of non-States Parties and the to and fro of political alliances by major countries with interests in maintaining good relations with African states. It may thus be possible for the non-compliance of a States Party to effectively go unpunished at an international level. In its 2015 report to the UN, the ICC noted that “the capacity of the [UNSC] to refer a situation to the Court is crucial to ensure accountability, but without the necessary follow-up, in terms of ensuring cooperation ... justice will not be done”. Historically, the UNSC has been slow to respond to non-cooperation communications from the ICC.

Therefore, the route of UNSC referral may not be viable where matters have originated in the UNSC given its politicised nature and questionable track record as far as cooperation communications are concerned.

Referral to the Assembly

Article 112(2)(f) of the Rome Statute empowers the Assembly to consider questions relating to non-cooperation. However, the scope of the Assembly’s powers is limited. In its Procedures Relating to Non-Cooperation (Non-Cooperation Procedures), the Assembly notes that any response by it to a referral from the ICC would be non-judicial and limited to its competencies under article 112 of the Rome Statute. It further notes that it “may certainly support the effectiveness of the Rome Statute by deploying political and diplomatic efforts to promote cooperation and to respond to non-cooperation. These efforts, however, may not replace judicial determinations to be taken by the Court”.

The Non-Cooperation Procedures document does not set out what the Assembly may actually do beyond a formal or informal response through a series of letters and meetings aimed at encouraging cooperation and accounting for non-cooperation by a States Party. Article 112 of the Rome Statute, which restricts the Assembly’s powers, authorises the Assembly to ‘take appropriate action’ in relation to reports of the Bureau of the Assembly. However, it is unclear from the Rome Statute and from the Non-Cooperation Procedures quite what ‘appropriate action’ is or may be.

The unfortunate conclusion to be drawn is that the Assembly is not empowered to do anything beyond ‘deploying political and diplomatic efforts’. This would be of little comfort to a relocated witness whose safety is at risk. Apart from this apparent impotence, there is the problem of the long delay between the act of non-cooperation and receipt of the referral by the Assembly inherent in its procedures. This all seems to suggest that, at best, some form of retrospective censure is the only real power which can be exercised by the Assembly, rather than the more helpful prevention or remedying of the actual non-compliance.

As far as non-States Parties are concerned (which the exiting states will eventually be), article 87(5)(b) of the Rome Statute provides that the cooperation request procedures (including referral to the Assembly) may be followed where the Court has entered into an agreement with a non-States Party. Therefore, the concerns raised above are equally applicable in the case of future relocations to these states on the basis of ad hoc relocation agreements.

The overarching conclusion that can be drawn from this is that the Rome Statute itself does not contain an effective solution to the problem of non-compliance in relation to protection of relocated witnesses. The next alert will consider whether a solution may lie elsewhere.

The information and material published on this website is provided for general purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. We make every effort to ensure that the content is updated regularly and to offer the most current and accurate information. Please consult one of our lawyers on any specific legal problem or matter. We accept no responsibility for any loss or damage, whether direct or consequential, which may arise from reliance on the information contained in these pages. Please refer to our full terms and conditions. Copyright © 2026 Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr. All rights reserved. For permission to reproduce an article or publication, please contact us cliffedekkerhofmeyr@cdhlegal.com.

Subscribe

We support our clients’ strategic and operational needs by offering innovative, integrated and high quality thought leadership. To stay up to date on the latest legal developments that may potentially impact your business, subscribe to our alerts, seminar and webinar invitations.

Subscribe