A fair share approach equals success in the extractives industry

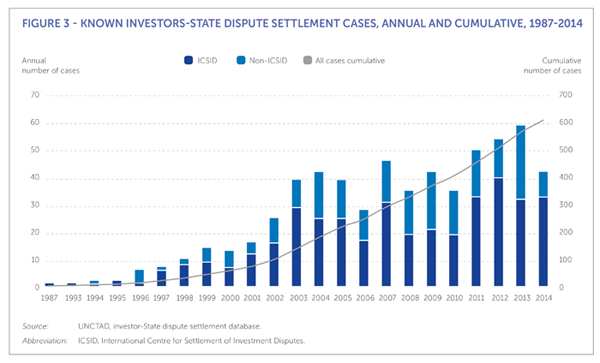

A review of various public reports in respect of disputes within the extractives sector (mining, oil and gas) suggests that there has been a significant increase in disputes between investors and host governments. It appears, more than ever before, that disputes in the sector have resulted in international arbitration.

These tensions are mainly due to the fact that governments and investors will always be “competitors” when it comes to what constitutes a “fair distribution” of revenue and profits between the host government and the investor. There is however an additional layer which is always disregarded – the benefit communities derive from companies extracting resources on their doorsteps (the so-called “social licence” to operate). The escalating tension is an indication that existing contracts between investors and host governments are not working and need to be reviewed. These include outdated domestic regulatory provisions of host governments, revenue distribution, profit share and community benefits.

A report by Chatham House released in November 2013 suggests that:

“during 2001 and 2010, arbitration cases for oil and gas increased more than tenfold compared with the previous decade, while those for mining increased nearly fourfold. This dramatic increase reflects escalating tensions among stakeholders involved in the sector, culminating in disputes that have been difficult to resolve in a cooperative manner.”

The chart below provides an indication on the rise of investor disputes over the past 28 years.

It is recommended that with a greater number of mega projects in the resources sector still on the cards for Africa, mechanisms which will defuse future tensions and disputes, Chatham House’s recommendation between investors and host governments should be considered. Some of the proposed mechanisms include:

-

flexible contractual arrangements with built-in response mechanisms to changing market conditions;

-

simplified tax and regulatory frameworks for investors;

-

concise mining and petroleum laws that standardise licensing frameworks in various jurisdictions;

-

raising standards of governance; and

-

planning together and defusing tensions.

During the life-cycle of a resource project it is inevitable that the bargaining power will shift from the investor (capital and skills) to the host government after the investment costs are sunk. It is therefore important to have a holistic approach in understanding, among other things:

-

The host government’s short, medium and long term expectations and needs, which is sometimes difficult depending on the developmental status of the country

-

The community’s within which the company intends to operate and meeting its expectations and needs (a “social licence” to operate).

-

The labour and employment conditions.

-

General regulatory and socio-economic risks.

-

Mitigation measures in terms of bilateral or multilateral treaties, or if none, whether the domestic legislation is sufficient in providing protection to investors in the event of, among others, expropriation by the host government or a dispute with the host government.

It is important from a dispute resolution perspective for foreign investors (including intra-African investors) that African governments also foster a harmonised system for the settlement of international commercial disputes aligned with the United Nations Commission in International Trade Law Model on International Commercial Arbitration. The current systems for the settlement of international commercial disputes are fragmented and require a concerted effort by African leaders to harmonise. This is important for both investment flow from outside Africa and intra-African trade.

As more accessible mineral and hydrocarbon reserves continue to dwindle, the exploitation of minerals and hydrocarbons will increasingly take place in challenging regions where the regulatory and political risk is uncertain. These uncertainties must be carefully assessed by investors. From the outset, it is imperative for an investor in so-called challenging regions to establish a long term strategy between all stakeholders (investors, government, community, potential labour etc). This relationship must be mutually beneficial (“fair share” approach and transparent) and inclusive in order to mitigate and defuse future tensions after the project costs are sunk. This does not guarantee that no tension will arise, but at least it ensures that the relationship between the investor and host government starts on a transparent basis, setting-out realistic and fair expectations between each stakeholder in the extraction of mineral or petroleum resources during the entire project life-cycle.

The information and material published on this website is provided for general purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. We make every effort to ensure that the content is updated regularly and to offer the most current and accurate information. Please consult one of our lawyers on any specific legal problem or matter. We accept no responsibility for any loss or damage, whether direct or consequential, which may arise from reliance on the information contained in these pages. Please refer to our full terms and conditions. Copyright © 2026 Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr. All rights reserved. For permission to reproduce an article or publication, please contact us cliffedekkerhofmeyr@cdhlegal.com.

Subscribe

We support our clients’ strategic and operational needs by offering innovative, integrated and high quality thought leadership. To stay up to date on the latest legal developments that may potentially impact your business, subscribe to our alerts, seminar and webinar invitations.

Subscribe