A snapshot of South Africa’s draft Integrated Resource Plan 2023

At a glance

- The Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy recently announced the extension of the commenting period for the draft Integrated Resource Plan 2023 (Draft IRP) to 23 March 2024.

- Despite the myriad of concerns surrounding the Draft IRP, it is important to remember that the intention of the document is to invite comments and scrutiny, so as to ensure that its final version, once promulgated, speaks to what is achievable and, as far as possible, acceptable.

- The Energy Council of South Africa has hinted at significant revisions that may follow, noting that "it will be unacceptable to have a national policy guideline that still has significant load-shedding in 2030".

The purpose of the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) generally is to provide a roadmap for meeting South Africa’s forecasted electricity demand, which integrates financial considerations with the country’s climate change commitments to ensure a sustainable and economically viable energy supply solution.

Presently, the IRP that was formally gazetted in October 2019 (IRP2019) remains applicable. However, since its publication, the energy sector has been inundated with developments and challenges that have rendered the assumptions underpinning the IRP2019 moot, thus mandating its (long-overdue) review.

IRP2023 Horizons

The Draft IRP considers the country’s planned electricity pathway across two successive timeline trajectories, namely Horizon 1 and Horizon 2.

Horizon 1 (2023 to 2030)

Horizon 1 sets out the short-term action framework, with interventions planned up until 2030 that are aimed at addressing the current energy generation shortfall by reducing unserved energy (i.e. measure of demand that cannot be reliably met due to supply-side shortages – or rather, load-shedding).

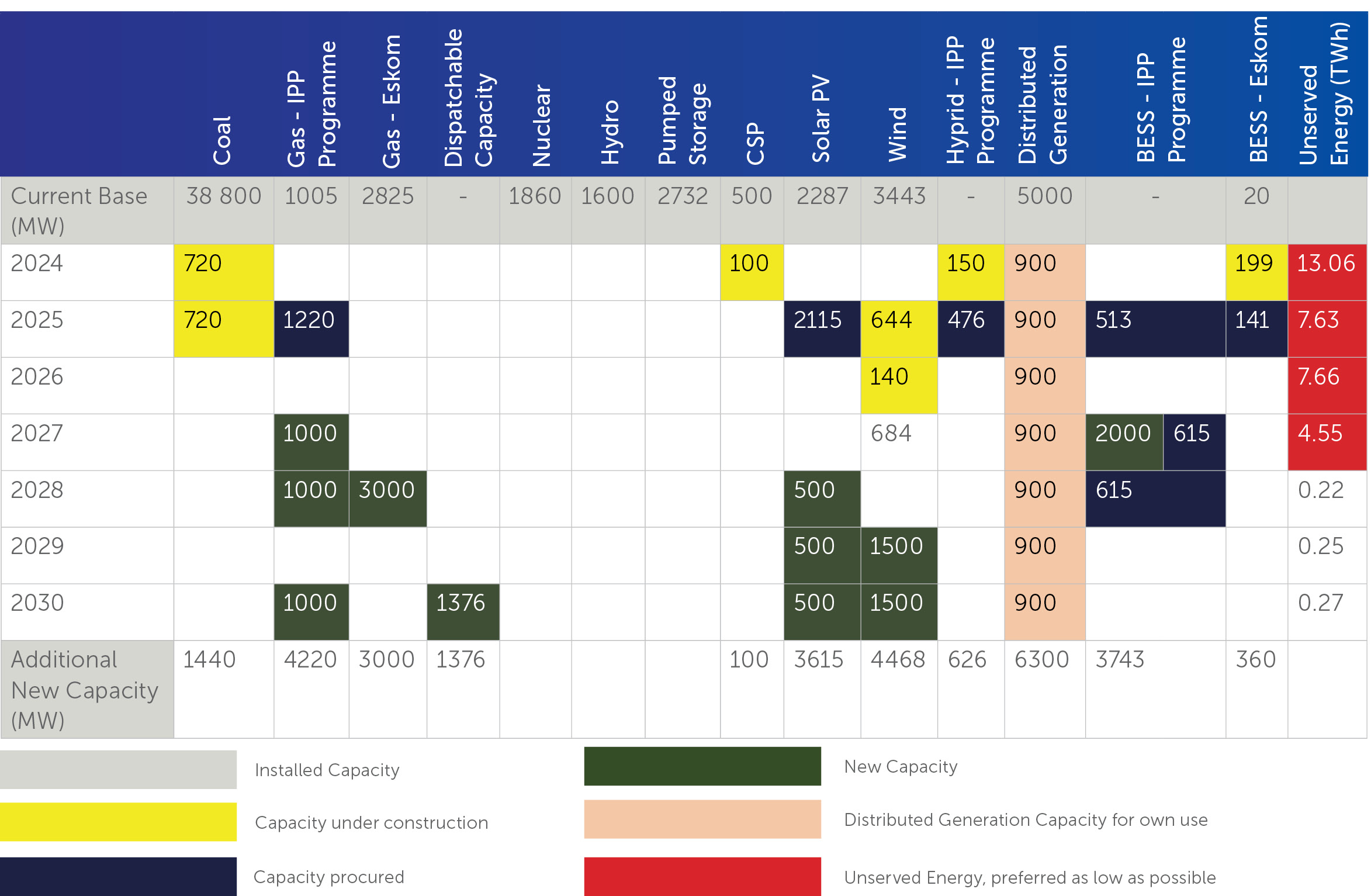

Having assessed five energy pathway scenarios, each comprising of different variations of private and public electricity generation interventions, the following plan has been put forward as the preferred proposed course of action with the lowest levels of unserved energy:

According to the Draft IRP, this plan is premised on certain key observations and interventions, including:

- Improvement of the energy availability factor (EAF) of Eskom’s coal fleet.

- Deployment of gas-to-power solutions as a means to add dispatchable generation. This will be essential to address the unserved energy risk, as reliance on non-dispatchable supply initiatives (i.e. wind and solar PV, excluding storage options) is not sufficient.

- Extension of the life of certain coal-fired power plants that were due to be decommissioned, as well as completion of the extension of Koeberg Nuclear Power Station’s design life.

- Implementation of the grid initiatives per the Transmission Development Plan 2023–2032 (TDP) to unlock grid capacity to allow more new generation capacity to connect in grid-constrained areas.

What is evident from the plan is that, in a best-case scenario (i.e. assuming an improvement of Eskom’s EAF), load-shedding is set to continue until at least 2027. As stated in the Draft IRP, “while ongoing additional generation capacity initiatives are expected to alleviate unserved energy, they do not fully address the underlying system adequacy”.

Horizon 2 (2032 to 2050)

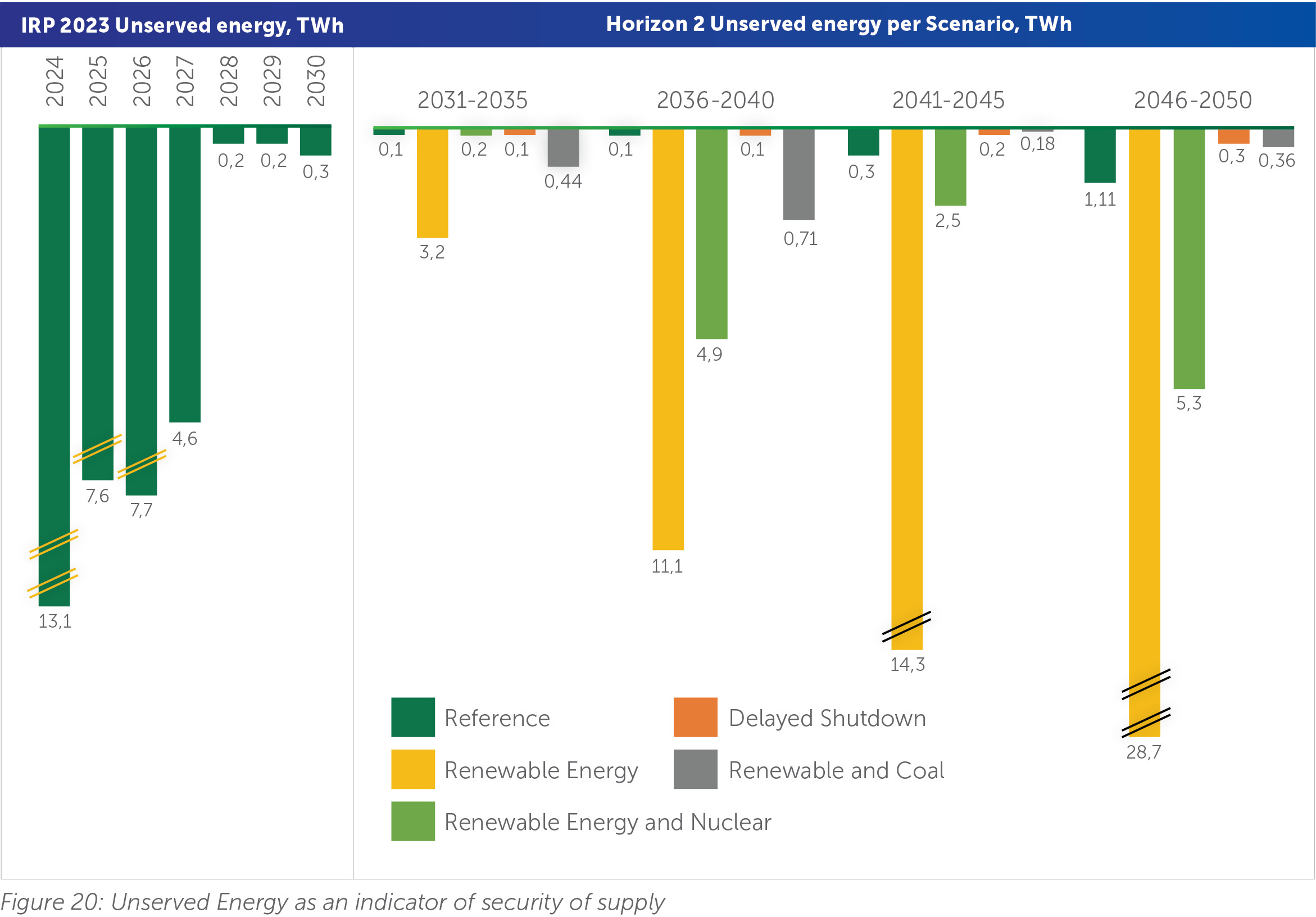

As with Horizon 1, various energy mix pathways were considered for Horizon 2, comparing combinations of gas, wind, solar PV, nuclear, battery storage and cleaner coal technologies. Taking into account security of supply, overall system costs and the need to minimise load-shedding, of the five scenarios assessed for Horizon 2, the Draft IRP concludes that:

- Renewables and clean energy technologies cannot in insolation sustain security of supply. A combination of dispatchable technologies – including nuclear, clean coal and gas – that support carbon reduction commitments, is required.

- A significant new build programme is required to meet demand for the 2032–2050 period, which is dependent on successful implementation of the TDP.

Looking purely at unserved energy, the diagram below serves to illustrate these findings, where the reference pathway includes a new build programme comprised mainly of solar PV, wind and gas.

Importantly, this needs to be considered and understood against decarbonisation trajectories and overall system costs as set out in the Draft IRP. That being said, it nevertheless serves to illustrate the importance of securing a sustainable, diversified energy mix that is capable of providing stability, adequacy of supply and sustainability.

General comments

Lack of transparency: Lack of transparency has drawn significant criticism from stakeholders, as the economic assumptions that underpin the modelling done for the Draft IRP have not been made publicly available. While the sources of data and the underlying assumptions were addressed during the virtual public engagement workshop held by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) on 31 January 2024, concerns remain that the Draft IRP lacks sufficient information to allow for proper public scrutiny.

Exclusion of green hydrogen: The Draft IRP does not explicitly mention green hydrogen as part of the potential baseload options that can also contribute to the transition towards cleaner energy. This does not align to with other national policy instruments, including the Green Hydrogen Commercialisation Strategy. It is essential for our policymakers to explore advancements made by market leaders in this field, including fuel cell technology, which converts hydrogen directly into electricity. Recent developments in gas turbines and combined cycle power plants also evidence the ability to integrate hydrogen as a sustainable fuel source for baseload and peak power generation.

Fewer renewables for Horizon 1: Compared to the IRP2019, it is evident that renewables comprise a much smaller component of the total energy mix leading up to 2030. Excluding private sector initiatives, the total installed capacity for solar PV has been reduced from 8,288 MW to 3,615 MW, with wind down from 17,742 MW to 4,468 MW. However, it is important to remember that the IRP2019 has proven to be premised on certain unfounded assumptions, including underestimation of the trade-offs inherent in prioritising decarbonisation over energy security. Furthermore, the IRP2019 is understood to have over-estimated South Africa’s capacity to integrate large-scale renewable energy sources, particularly given existing grid limitations.

Decarbonisation challenges for Horizon 1: The prioritisation of coal and gas under Horizon 1 to improve the EAF and reduce unserved energy brings into question the country’s ability to meet its decarbonisation commitments under the Paris Agreement. The Draft IRP expressly recognises the difficulty of the coal fleet meeting the Minimum Emission Standards by April 2025 as an emerging risk. Stakeholders, however, need to bear in mind that studies have shown that over-reliance on non-dispatchable energy resources like wind and solar PV could destabilise the grid. To ensure security of supply in the short term, reliance on non-renewable energy resources thus seems inevitable.

EAF improvement for Horizon 1: While the Generation Recovery Plan is core to the President’s Energy Action Plan (and now also the Draft IRP), there are naturally doubts as to whether this is achievable. The IRP2019 was premised on a 75% EAF, which proved to be wholly unrealistic, as the EAF in 2023 averaged at around 54%.

Grid development dependency for Horizon 2: The dependence of Horizon 2 on implementation of the TDP is a noteworthy risk, as it remains unclear how the Government intends to fund the necessary grid upgrades and expansion, which is estimated to require around R390 billion. While various options are being explored, including involvement of the private sector and establishment of an independent procurement office for transmission infrastructure, the lack of clear solutions and timeframes is concerning. The current TDP is also based on the IRP2019 and will have to be revised once the Draft IRP is finalised and promulgated.

Conclusion

Despite the myriad of concerns surrounding the Draft IRP, it is important to remember that the intention of the document is to invite comments and scrutiny, so as to ensure that its final version, once promulgated, speaks to what is achievable and, as far as possible, acceptable. The public is therefore encouraged to submit their comments during the extended commenting period. Moreover, based on its own modelling exercise and recent engagements with the DMRE, the Energy Council of South Africa has hinted at significant revisions that may follow, noting that “it will be unacceptable to have a national policy guideline that still has significant load-shedding in 2030”.

The information and material published on this website is provided for general purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. We make every effort to ensure that the content is updated regularly and to offer the most current and accurate information. Please consult one of our lawyers on any specific legal problem or matter. We accept no responsibility for any loss or damage, whether direct or consequential, which may arise from reliance on the information contained in these pages. Please refer to our full terms and conditions. Copyright © 2024 Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr. All rights reserved. For permission to reproduce an article or publication, please contact us cliffedekkerhofmeyr@cdhlegal.com.

Subscribe

We support our clients’ strategic and operational needs by offering innovative, integrated and high quality thought leadership. To stay up to date on the latest legal developments that may potentially impact your business, subscribe to our alerts, seminar and webinar invitations.

Subscribe